As a child, every morning, Ehren Clark got put on a special bus and shuttled off to the Gifted

and Talented school. He was handsome. A charmer. Artistic and fashion forward. He’d grow to

be 6’4, a great swimmer and excellent student, and the manager of a bakery while still in high

school. He graduated from college, got his masters, and began a successful career. He had all

of the brains, talent, and charisma to do whatever he wanted in life, but according to his big

sister, Sarah, “The world crushed it out of him. It’s kinda not fair.”

Sarah Clark Davis is the oldest of six siblings who grew up in Houston, TX. She always shared

a special closeness with second-in-line, Ehren, even when things got complicated toward the

end of his life. Their dad came from LDS pioneer roots; their mother, Joanne, was a convert

who jumped in headfirst and embraced everything about her newfound faith. Joanne’s kids’

aptitude for art and fashion trickled down from her side, which included several LGBTQ

members: a brilliantly creative artist and gay uncle who died of AIDS when Sarah was 14, a

lesbian aunt, and a trans cousin. Growing up, Sarah says Ehren, “was always the good kid,

mom’s favorite. He made us all look bad. If we ran out to play, he’d stay back to clean the

kitchen. It was obnoxious -- he always did the right thing in church, school, home. Until he

didn’t.”

Around age 15, things fell apart. Ehren started failing school and failing to come home. He loved

music and dancing and would go out to clubs all night with an older crowd, returning home in

Depeche Mode-esque eyeliner. Sarah says, “There was never a moment he sat me down and

said, ‘Sarah, I’m gay.’ I would have been like ‘Yeah, I know.’ He was just open with himself in a

way that everyone knew this guy was gay. And he wasn’t afraid to be his flamboyant self.”

Growing up in Texas, Sarah remembers defending Ehren against name-callers who made fun of

the way he ran. He gravitated toward safer pursuits and really found his people in the theatre

community. There was never really a conversation about him going on a mission – by that age,

Ehren was out on his own path. He remained close to his family, especially his mom, but longed

for a family himself. Sarah noticed a grief she assumes was impacted by his inability to

reconcile his life with church teachings.

All of Ehren’s siblings went to BYU, while he went to the U. Shortly after, he backpacked

through Europe, where his troubles escalated and he had a substance abuse-related

breakdown. “The drugs were not helpful to the issues he already had going on in his brain,”

says Sarah. He was admitted into a hospital, where he was diagnosed with drug-induced

schizophrenia and bipolar, what's often referred to as schizoaffective disorder.

Ehren returned to Utah, where he found the church’s addiction recovery program useful in

helping get his substance abuse under control. After earning a masters in art history from

University College London, Ehren became very active in Salt Lake’s arts community – teaching

at Westminster College, and befriending artists and gallery owners alike while working as an art

critic for City Weekly. Sarah says, “He loved that life and community so much.”

All the while, Ehren’s family focused on loving and supporting him with zero unrealistic

expectations. They adopted the “we don’t know how this will work out in the church, but it will”

approach. Even after he stepped away at age 18, Sarah was always comforted by the many

people on various ward rosters who continued to reach out to Ehren throughout his life and

show him love. “I realize it’s a lottery and not everyone has that in the church, but I want to do

what I can to provide that where I attend – to leave the doors as wide open as possible so

people feel wanted.”

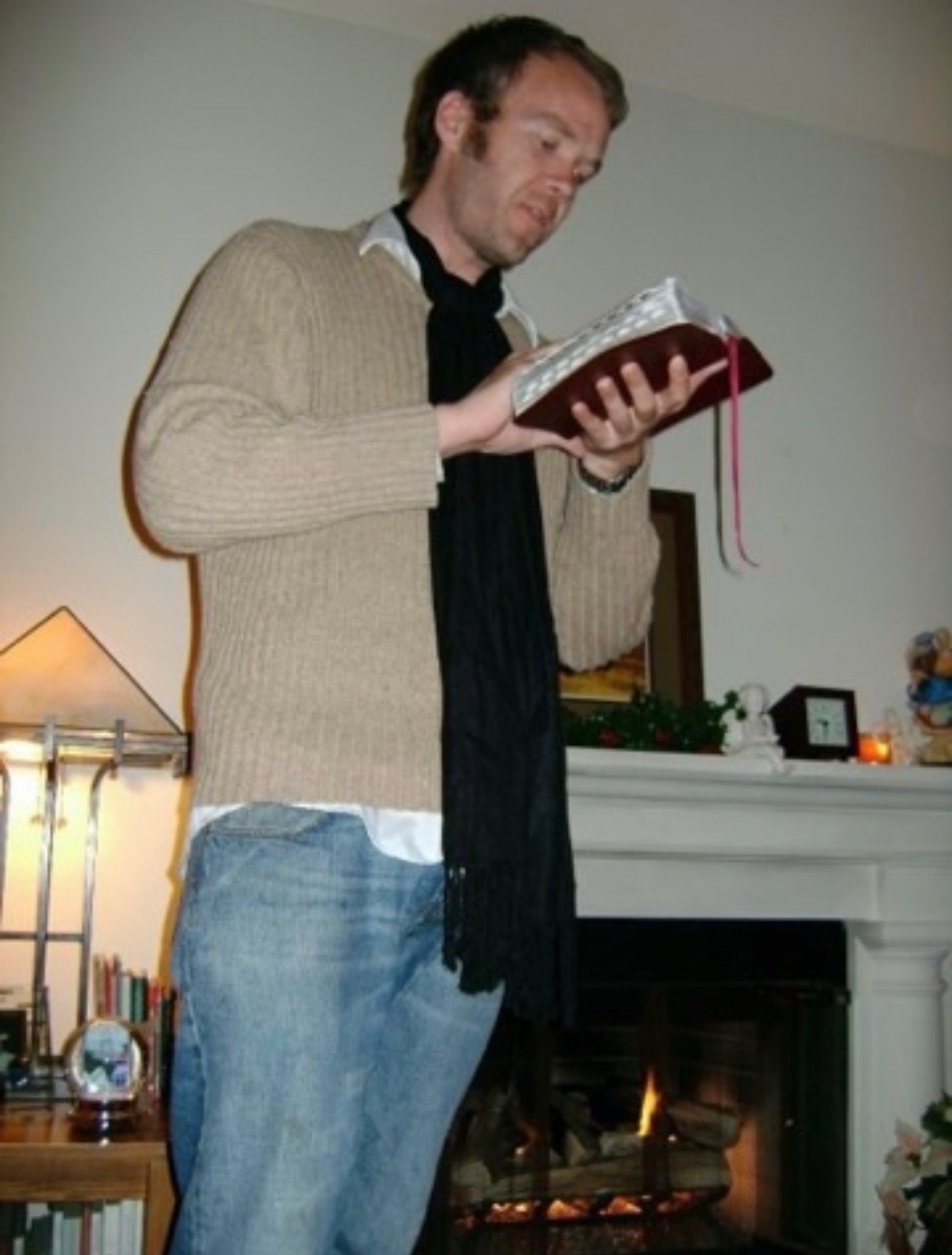

To his family’s shock, after nearly two decades of being out of the church, around age 36, Ehren

was ushered back in by a faith community Sarah describes as his “angels.” She says he lived in

this “funky little branch in Salt Lake that was filled with diversity, artists, and he found his people.

The bishop just loved him, and Ehren went back and became the assistant executive secretary.

Then he called us up one day to invite us to his endowment exactly thirty years from the date of

his baptism.” Sarah still marvels that her brother chose to quit drinking, smoking and even

coffee to go to the temple especially since all of that was part of his social circle. But she says

his complicated mind longed for a peace he somehow found in the temple -- where he worked

weekly up until he died.

Toward the end of his life, Ehren also worked at the enterprise Sarah founded, Fashionphile,

where he’d pen product descriptions for resale luxury goods. Loving fashion the way he did,

Ehren had a flare for the words that described it, though his mental health sometimes impeded

his productivity. Of his output, Sarah laughs, “We just figured, it is what it is. At the end of the

day, we’re going to get something, even if it may need a little editing!”

Sarah had a startling dream one night in which both she and Ehren had died, and he joined her

at the pearly gates in the form of the handsome, smart, witty, cool guy she’d known when he

was younger and before his mental break. He said, “What happened? Right when I needed you

most, you backed away.” Sarah woke up in a sweat and thought if Ehren had cancer, she would

have moved him in with her family. From that moment, she made a concerted effort to strip any

boundaries that might prevent her from being there for him, even when he was difficult.

As Ehren lived alone, Sarah and her sister initiated daily FaceTime calls with him. His mood

swings were extreme. In the same call, he might put them on a pedestal, then start swearing

and call them she-devils. Sarah mastered the art of, “Ehren, I love you. I can tell this isn’t a good

time. Let’s talk later.” And they would. To this day, Sarah is still triggered by the sound of a

FaceTime call, remembering the beautiful face and complex mind of the brother she loved.

2017 was not a good year for Ehren or the Clarks, especially on the tail of their father’s

diagnosis with brain cancer and onset of their mother’s dementia. In an attempt to convince

them he was okay, Ehren had pulled away a bit from the family, while also exhibiting extreme

mood swings and weight fluctuation – his meds out of balance. But Sarah and siblings thought if

they could just get him through their annual 4th of July gathering at their family cabin, they could

work together to get him admitted somewhere and get his meds regulated.

Right before the gathering, Sarah called, but Ehren didn’t answer. Their brother, Jesse, went

over to check on him and Sarah says as he walked up the stairs, he says he felt a heaviness.

He just knew. They all did. At 42 years old, Ehren was gone. Jessie found him in bed in his pj’s

and his slippers at the bedside. His room was tidy and his cat was curled up next to him. Ehren

had overdosed on the wrong medicine cocktail – his dosage off. It still plagues Sarah how easy

it is for some to overdose on prescription medicine.

Reflecting on the tragic loss of her brother, Sarah says, “It’s all interconnected – part of his

mental illness and personal tragedy was his never being able to accept that constant tension in

his brain – his sexuality against his testimony. He loved being ‘a Mormon.’ What does that mean

for your brain if you love that, and you’re gay?” Sarah acknowledges there are many things

about Ehren’s life she doesn’t know. She guarantees there was likely a plethora of hard stories

involving bullying and nastiness that she wasn’t privy to. She reckons, “I’m sure it was there. I’m

sure there were people who weren’t nice. But I also know he was blessed with a lot of angels

who loved him.”

Meanwhile, Sarah is grateful for her lesbian aunt who lives a great life in Poway as a diehard

Dodgers fan and successful, contributing member of society. But most importantly, she’s always

been a friend and support to Sarah. She has modeled a loving openness that has inspired the

Davis family. She freely shares her own mission stories and has always been encouraging to

Sarah and her kids when they've embarked on their missions. And in turn Sarah and her family

have done their best to follow her example, showing love and support to their trans cousin after

having top surgery. “Post-surgery, my aunt thought it was cool their Mormon family was doing

what they do best, and sending over dinner.”

Sarah regrets that Ehren’s path was more difficult as he battled a series of heavy things -- his

eating disorder, his schizo-affective diagnosis, his drug addiction. “Maybe if just one of those

things wasn’t there, he could have just been himself and done anything.”

Every December, Sarah’s family now decorates a Christmas tree in rainbow décor in her

brother’s honor. “He loved attention - for his amazing outfits, for who he is. And he’s in heaven

right now loving that we’re talking about him.”