Jason Cooper’s childhood home was one that tackled hard things with humor. So in hindsight, it was a little comical to his mom that one day while sitting in the living room in the dark in serious discussion with her (gay) husband, he blurted out, “If I have to stay married to you for one more day, I’ll kill myself. Don’t take offense to that.” Jason’s mom, Janet Rawson, had known her husband Farris was attracted to men for over a decade, but not before their wedding day. Back then, in the 60s-70s, Jason says it was common to grow up with the mindset to “do your duty in the church—serve a mission, marry in the temple, have kids.” And that’s what the Coopers did. Jason was four years old when the dissonance his father was struggling with became too much and he revealed this part of himself to Janet. Another decade later, Jason’s father sat his oldest three kids down to tell them that he’d been excommunicated from the church, but didn’t get into too much detail about why. While Farris told his kids not to let that affect or skew their standing in the church, he encouraged them to find out for themselves whether it was true. He and Janet told their children a few years later that he and Janet were divorcing. The kids also learned they would be staying with their mother, and Jason’s dad warned them not to give her any trouble.

After an atypical divorce, the family dynamic continued in an atypical way, with Jason’s dad “walking in Christmas morning to the house he was no longer a part of to open gifts with us. He was at all the big things he could be, while living 200 hundred miles away in Salt Lake City.” When Jason was 17-years-old, his father finally came out to him. Jason replied, “You’re still my dad and I still love you.” Eventually, Farris introduced his kids to the partner he’d been living with in Salt Lake. From then on, the couple remained an important part of Jason’s and some of his siblings’ lives. Farris’ partner had also grown up LDS in small town Wyoming and served a mission to Mexico City, and Jason fondly remembers him being the one to purchase most of Jason’s mission clothes. Jason met his wife Stephanie on their respective missions to Tucson, AZ. Near the end of Jason’s mission, he developed feelings for Stephanie and he knew he’d need to feel out whether his dad’s relationship would be a dealbreaker for her. Luckily, it wasn’t, and Jason now laughs at how Farris’ partner would leave food for the young couple in the fridge when they’d come over, with notes like, “Remember who you are and why you’re standing. If you’re not standing, you’re not remembering. Signed, love your wicked stepmother.” While Jason’s father passed in 2007, Farris’ partner is still a part of the Coopers’ lives, and they regularly spend holidays together. But when it comes to celebrating his birthday, Janet laments, “It’s hard because I can’t find a card that says, ‘Happy birthday to the man who stole my husband’.”

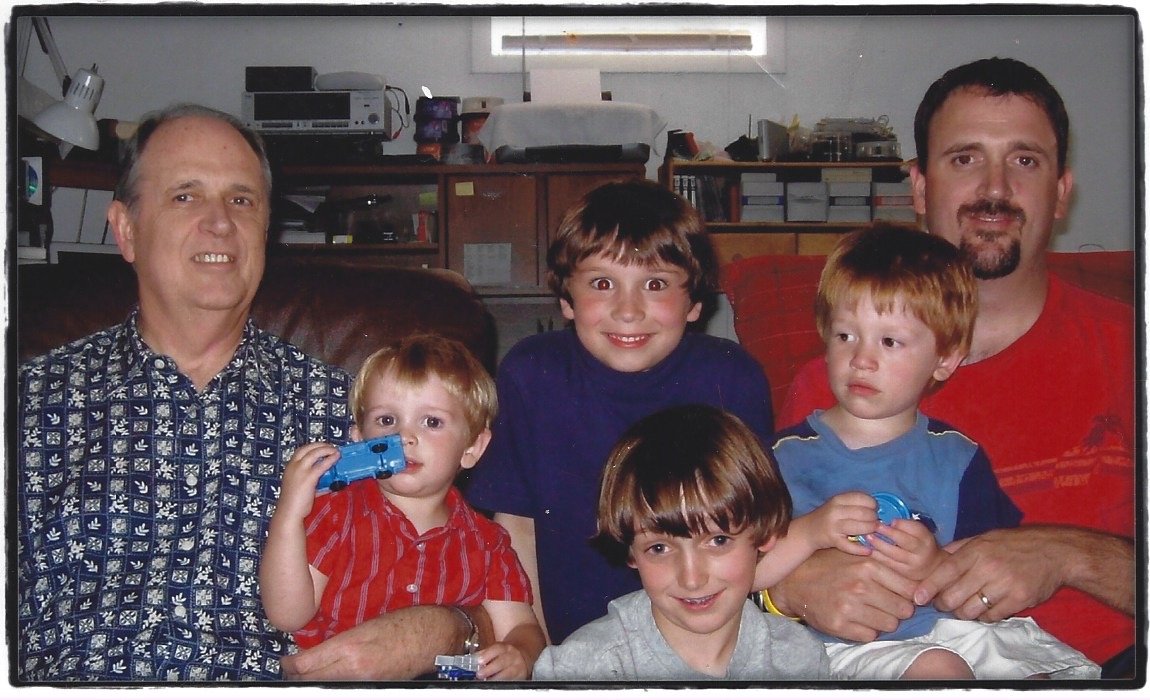

Jason and Stephanie Cooper have raised their five kids (Tucker—27, who is married to Mikayl—25, Cole—24, Ben—19, Lola—15, and Grace—11) between Salt Lake and Idaho Falls, ID, where they now reside. A special memory for their two oldest boys was getting to run errands with Grandpa Farris and his partner in SLC when they were younger, and Stephanie and Jason were at work and school respectively. Tucker and Cole would join the men on errands as they picked up supplies for their cosmetology practices and took them to restaurants like the Soup Kitchen and Skool Lunch where employees would gush, “Where are your boys?” Later on, these memories of the gay grandpas being mostly accepted (but often not in mostly conservative Utah) would prove a significant impact on Cole, who would later navigate his own orientation.

From a young age, Cole was known as the Cooper family’s second mother and the one appointed caretaker of his siblings when his parents were away. His friends would jokingly call him the “old lady,” because when they’d go swim in the river, he was the one elected to hold their phones and towels and make sure they didn’t do anything too stupid. In high school, Cole played drums and percussion in the band and was involved in student council-- “a typical kid,” says his father, though “remarkably mature.” Cole started to figure out his sexuality around age 12, and by age 14, was texting a friend about how cute a guy was. Stephanie was checking to make sure that Cole’s phone was turned in for the night when the text message came in, and seeing this message sparked a conversation in which he came out to her, but told her “not to tell dad.” Jason’s not sure why this was Cole’s instinct, especially regarding his open acceptance and love for his own father, but wonders if perhaps there was something non-affirming he had said that his son had picked up on? Stephanie agreed Cole should be the one to tell Jason, and Cole waited until he was 18 to deliver what Jason describes as an organic conversation, “nothing like a big gender reveal or mission call opening.” As he had when his father had come out to him, Jason calmly replied, “It’s okay; I still love you—you’re my son.” Jason said his only sorrow expressed in this conversation was that there might be many people in their faith community who would reject the opportunity to get to know how amazing Cole actually is, after learning this one fact about him.

Just as Farris had been raised to do his duty to be faithful in the church, so had Cole. He assured his father, who was the bishop at the time, that while he had spent his life preparing for a mission, out of respect, Cole would not be seeking the Melchizedek priesthood, knowing its associated covenants were not something he would be able to honor. He and his parents now extend a mutual respect to each other’s varied beliefs and church affiliation. Jason says, “Cole knows that if there are things that prick him—policies, procedures—he can talk to us about it. He’s never asked us to choose one or the other, and we would never ask the same of him.”

Cole is now studying Communication Disorders at Utah State University in Logan, and is interested in pursuing a doctorate in audiology after he gains some work experience. His siblings have always proven supportive, especially older brother Tucker, of whom Jason says, “I always wondered if they’d ever become friends, but now Tucker is his fiercest defender.” Jason was also touched when his youngest child, Grace, found out about Cole’s orientation and simply said, “That’s ok. You love who you love.”

As a “fairly sizable introvert” who has been told he comes across as “intimidating,” Jason admits he didn’t ask too many questions about Cole’s personal life until he was called out in this last year. While visiting one weekend, Cole asked, “Is there a reason you never ask about my dating life?” Jason said he just figured if there was something Cole wanted them to know, he’d tell them. Cole then revealed he’d been dating a guy for over nine months. Cole’s boyfriend also has an LDS background, and Jason says the two make a great couple and complement each other very well. Jason also feels he owes a debt of gratitude to the “extremely loving group of like-minded friends in Logan that Cole found—folks in the LGBTQ+ community who I think probably saved his life.” After a camping trip last year, the group spent an evening in the Coopers’ home, and Jason calls them all, “great, great people.”

Jason makes it a point to make his allyship known in his ward, wearing a rainbow pin on his lapel every week. Stephanie does the same. When a Harley-riding, “rough customer type” asked him why they wore the pins, Jason replied, “Why not?” The man responded, “Hmm, okay,” and sauntered off. While still serving as bishop, Jason felt inspired to teach a fifth Sunday lesson in which he could address his congregation’s relation with those who are LGBTQ+. His ward council backed the idea, in the in time between the approval by the ward council and the fifth Sunday lesson, Jason was asked to also speak at an upcoming stake priesthood meeting. He was given cart blanche to talk about whatever he wanted, and while nervous that he felt compelled to share his personal experiences being his father’s son and his son’s father, Jason says his message about making more room at the table was well received. A native of Idaho, there were several men in the audience who had known Jason since his childhood, and he initially worried how they’d react. But several made concerted efforts to reach out afterward and tell him just how much his words mattered. In preparation for the fifth Sunday lesson in his ward, He deliberately let his facial hair grow to a scruffy state before the presentation, so he could feel “just a little uncomfortable—something our LGBTQ+ brothers and sisters likely feel showing up every week.” After Jason’s fifth Sunday lesson which centered on how to more fully embrace any on the margins—including LGBTQ+, divorced, widowed, and single parent members, Jason said a handful of youth and members—including a full-time missionary—privately came out to him, now trusting him as a safe space. Jason and Stephanie likewise cherish the safe space of their local LGBTQ+ support group, appropriately called Open Arms. The organization has recently become a non-profit called Open Arms of Idaho (openarmsidaho.org).

After Jason gave a fifth Sunday lesson in a neighboring ward, there were those, however, who showed they’re still learning or gave a little pushback behind the scenes. The mother of a close friend expressed how her family missed seeing Cole and asked Stephanie to “tell Cole we love him and miss him.” Stephanie replied, “You need to tell.” Now that Jason’s been released as bishop, more people seem to feel safe approaching him. Jason says he likes following Ben Schilaty’s advice to ask the LGBTQ+ person closest to you about their experience and just listen. “We get so caught up with who we think an individual is, and don’t listen to who they are—which is what we should be doing as Christians trying to follow the two great commandments. It’s pretty straight forward–love your neighbor. That doesn’t mean you have to like them all the time; my wife probably feels that way about me--but she always loves me.”

Jason continues, “I know the relationship I had with my father benefitted the relationship I have with my son. I can’t imagine the things my parents went through in the 80s, but I’m grateful for the experience, and have to think it was preparatory and helped foster a better relationship with Cole. I’m glad I didn’t have to start from zero. There’s always room at the table.”