Being voted out of your tribe is rarely the goal. But sometimes when difficulties arise, people elect to leave on their own. Such was the case for amiable, Provo-based elementary school principal, Sean Edwards, whose recent stint as a contestant on CBS’s Survivor Season 45 was cut short when he nominated himself to leave early after just four episodes. Originally a player on last fall’s most defeated tribe in Survivor history, the “Lulu Tribe,” after some initial setbacks, Sean moved to the opposing “Reba” tribe where he admitted he was ready to be done with the game at tribal council. While Sean later expressed regret at his decision to leave prematurely, he remains a huge fan of the show, and now with hindsight, honors the initial intention he had as a competitor looking to reclaim lost time—time he used to spend trying to be something he wasn’t.

Sean grew up in New Jersey, the son of a Chinese mom and a Caucasian dad. He greatly admires his younger sister, Krista, and his older sister, Elaine--who has autism and cannot live independently. As such, the family moved from their western state roots to settle in the Princeton, New Jersey area for his father’s work and the excellent healthcare facilities for neurodivergent individuals.

Growing up, Sean always relied on the solid foundation of trust he had with his parents, believing they had his best interests at heart. But he was terrified in high school to tell them he was gay, especially after an LDS friend from California he’d met on Myspace revealed when he shared the same news with his parents, they’d kicked him out of the house. But Sean’s mom quickly assured him they would never do that. She promised they would “figure this out together,” and Sean felt willing to follow her lead. While she expressed her love, Sean remembers two emotions surpassing the others that day as he could tell she felt sad and worried. He asked that she be the one to tell his dad, who Sean was afraid to disappoint, as the only son in the family. Rather, Sean recalls his father didn’t overreact, saying, “He is pretty pragmatic, but it took him time to process.”

The three decided to keep Sean’s news just between them as they considered the best next steps. His parents dug into what limited resources there were at the time and came back with a solution: conversion therapy. Or seemingly, therapy that seemed promising as it was led by an LDS man who claimed he had “overcome his gayness through a particular process.” Sean says, “As someone who’d grown up living the typical LDS lifestyle, I wanted more than anything to be straight, so I tried it, beginning at age 17.” He endured the therapy off-and-on for another five years, which he says ultimately engrained in him “that I needed to change a fundamental part of who I am to be considered good and kind and accepted by God and others. It messed with my mind, trying to seek approval from God by trying to change who I am.”

BYU Provo proved to not be a cultural fit for Sean. He was called into the Honor Code Office at one point and put on probation for a year because someone had snapped a picture of him at a gay club in Salt Lake City, where he would go dancing. “I needed that community of people like me so badly.” That trauma resulted in him swearing off all gay clubs in Utah out of fear. He remembers another time of being especially hurt when, as his ward’s gospel doctrine teacher (a calling often assigned to people like him working toward teaching degrees), he found out a selection of his peers came to his class and sat in the back just so they could make fun of his charismatic mannerisms and animated disposition. He had experienced something similar before – having been bullied in middle school and high school where people called him the f slur and one time, threw a garbage can at him and called him “gay trash.” But now, at “the Lord’s university,” it felt like his tribe had spoken. Sean says, “It was really unfortunate to think that people who were part of my community were attending my Sunday School class to make fun of me.”

Back home in Jersey, his two best friends from high school, Ivana and Shannon, had the opposite response when, after his freshman year of college, Sean came out to them. “They were so supportive of me being gay, but when I told them I didn’t know what direction this was taking me because having been raised LDS, I wanted to do that path, they were like, ‘Why? You’re gay; be authentic to who you are’.” Sean says, “It was such a diverse perspective from the first time I’d come out to my parents. I was glad they didn’t have the LDS lens so they could help me understand the full spectrum of support I needed.”

As Sean proceeded with his schooling, which culminated in him graduating from BYU and then, while simultaneously being a high school vice principal, earning a doctorate degree from the University of Utah where he did his dissertation on LGBTQ+ students and perceptions of connectedness in school communities, Sean realized that his experiences being marginalized had also led him to developing resilience, empathy, true compassion to others, and had provided him a growth mindset in which he could choose to be confident while also looking out for others who suffer along their way. They are all gifts that have helped Sean buoy the young students who now walk the halls at the school where they call him Dr. Edwards, their principal.

“Living in Orem and working in Provo as a public-facing person can be tricky. There have been multiple occasions where people have called the school secretary to express their concerns about their kids having a gay principal. It’s difficult because I love the students I work for and want them to have incredible experiences learning math, reading, STEM, all those great things. It’s hard to have people question my integrity.” Because of this fear, Sean didn’t come out to his professional peers until after he was working in an administration position.

Nowadays, Sean sees being gay as a huge blessing. Not only did his life story of navigating the challenges of being LGBTQ+ in a conservative religion contribute to him being selected to be a contestant on his favorite show, but he appreciated the fresh air Survivor island gave him to completely be himself and meet new people in a context in which he didn’t have to assume they were going to call the office on him. He says, “Even though it’s a competitive environment, the humanity is still there. I made really meaningful connections.” The bonds he created with all the players still linger via a vibrant, 18-person text chain, and Sean laughs that one of his closest friends from the show, Sabiyah, is a lesbian and Black former Marine turned truck driver from the south. He says, “We’re worlds apart in life experience and upbringing, but she became my #1 ally and best friend out there.”

However, the greatest gift being authentic has allowed Sean was meeting his husband on Facebook back in 2016, because “Who meets in real life these days?” Sean laughs. Matt also grew up in the LDS faith tradition, one of seven kids from Draper, UT. The two instantly connected. Their first date was a scary movie, and one of their initial connection points was their shared love for you guessed it: Survivor. (Matt had auditioned previously.) After a year of dating, Sean made it clear that he’d be ready to get engaged, and Matt proposed not once, but twice—the first time via a scavenger hunt around Provo guided by meaningful clues leading to places that meant a lot to the two of them, and then, very publicly onstage at a Naked & Famous concert in Aspen, CO, where Matt had pre-arranged with the band to be called up for the big event. They were married August 1, 2018 in Orem, and bought their first house together a year later. Matt now works for the U as a researcher for K-12 issues across the state, where he crosses paths with many professors from Sean’s graduate program.

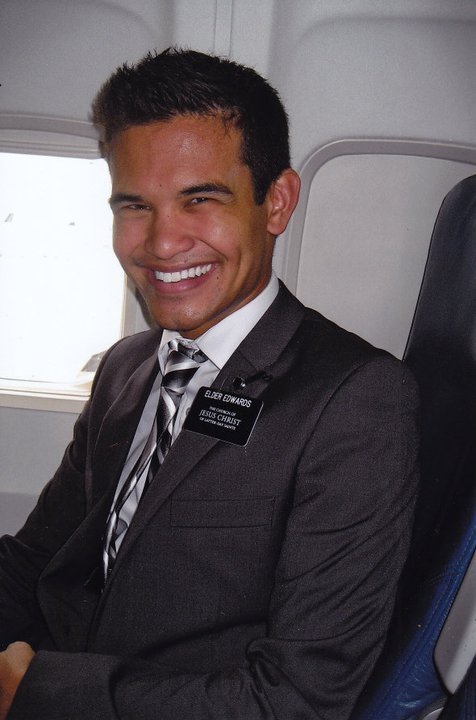

While the two no longer participate regularly in the LDS faith, Sean loved his Las Vegas mission (where he had the opportunity to connect with several members of his dad’s side of the family), and will now occasionally attend a friend or former student’s mission farewell or homecoming church service. He says he and Matt are “very consistent” in their daily prayer: “Having a strong relationship with our Heavenly Father and Jesus is important to us.” Affected by the positive and not so positive influences of the church community within which they were raised, they choose to bring aspects of their faith into their relationship, though try to create a safe space with their spirituality. At 5’6, with “not an athletic bone in my body,” Sean remembers not fitting into his ward youth group’s frequent basketball nights. If he could pass along any lived experience to church members and leaders, Sean says, “I wish church leaders knew how to love LGBTQ+ people. I’ve heard so many say that the decisions I was making were wrong or bad, much more than I’ve heard the message, ‘I love you’ or ‘The Savior loves you’. As LGBTQ+ people who grow up LDS, we know the church position on LGBTQ+ topics; we don’t need leaders reminding us again and again. What we need to know is our leaders and Heavenly Father and Jesus love us. I think because they tell us how we live is wrong or bad, they think it’s an expression of their love for us, but I want to be so clear in saying it’s not. You might think that, but if it’s not being received in that way, it does not resonate and is not a message of love.”

Luckily, Sean and Matt are able to fill their lives with the friends and family they love and who love them, which are plenty. Living so close to Matt’s family, who Sean says he adores, they see many local family members often. Sean believes he will also frequently continue to see members of his Survivor family. “I absolutely loved my Survivor experience. It was fun, inspiring, complex, challenging, beautiful—every emotion wrapped into one experience… What’s so interesting though is how it became this great metaphor for my life in general. I had prepared for years and years and wanted it for such a long time, since I was 11 or 12, but never had the confidence to try. Then, in 2020, I started submitting applications and after three years, got on. I had all these dreams of what might happen, but my tribe lost nearly every challenge and I did not win the game. And that’s life, you have all these expectations and convictions of how life will go, but it can go the opposite. Even though it’s not what you might have thought it would be, it can be beautiful. I wouldn’t be who I am today if I didn’t go through all the experiences I did, and it's the same with Survivor.”

Sean admits that he wishes he could have approached the moment of his departure differently, but after not eating anything but coconut and papaya (having no fire) and experiencing difficulty sleeping for nine days, “I wasn’t firing on all cylinders.” He concludes, “Sometimes we’re human, sometimes we make mistakes, and sometimes it’s on a national platform. I didn’t have to leave; I could have lived out my dream. But instead of allowing regret to drive me, I need to find a way to own it and learn valuable lessons from my mistakes. We must have the resilience to move forward.”

While he may not have ultimately won at Survivor, Sean was asked to emcee this June’s Utah PRIDE parade, where he recruited his husband and sister Krista to join him. As part of his celebration, he went to a Salt Lake City gay club for the first time since his BYU days, which he says, “felt like a reclamation. I’ve decided, I’m going to do me.” Having recently turned 36, Sean says if he could go back a couple decades to that teenage boy who dreamed about being on a reality competition show, he’d give him some valuable advice: “Prioritize connections with people who matter; find your tribe. You will be successful, happy, and you’ll find partnership and companionship. You won’t be lonely. It’s ok to take risks, try new things, and embrace failure. Who you are is beautiful.”

Photo credit CBS

Photo credit Robert Voets/CBS

Selected photos courtesy of CBS and Robert Voets/CBS, as noted above